I was giving a talk about fine art photography awhile back and one of the attendees thanked me for submitting my Fall Maple Leaf image to the Ward Museum’s 2017 Art in Nature Photography Competition. To my great surprise, the picture took the grand champion award. The attendee explained that my image was very different from the other entries and by winning the award, I opened the door to more experimentation and artistic expression.

I thought about that discussion when the Ward Museum asked me to give a lecture at their 2019 event. I asked myself why I won and what lessons could I share. First, I should make clear that while I photograph elements of nature and what I call the nature of things, I do not consider myself a nature photographer. There are many outstanding photographers who dedicate all of their time, energy, and resources to capture their favorite birds, bugs, plants, animals and landscapes including the masterful works of Denise Ippolito, Art Wolfe, Frans Lanting, Thomas Mangelson, and Paul Marcellini. Many of the best nature photographers have a sense of purpose in their work, capturing images that are intended to bring awareness of climate change, studing the behavior of animals, advocating for endangered species, or they simply want people to enjoy the wonders of nature.

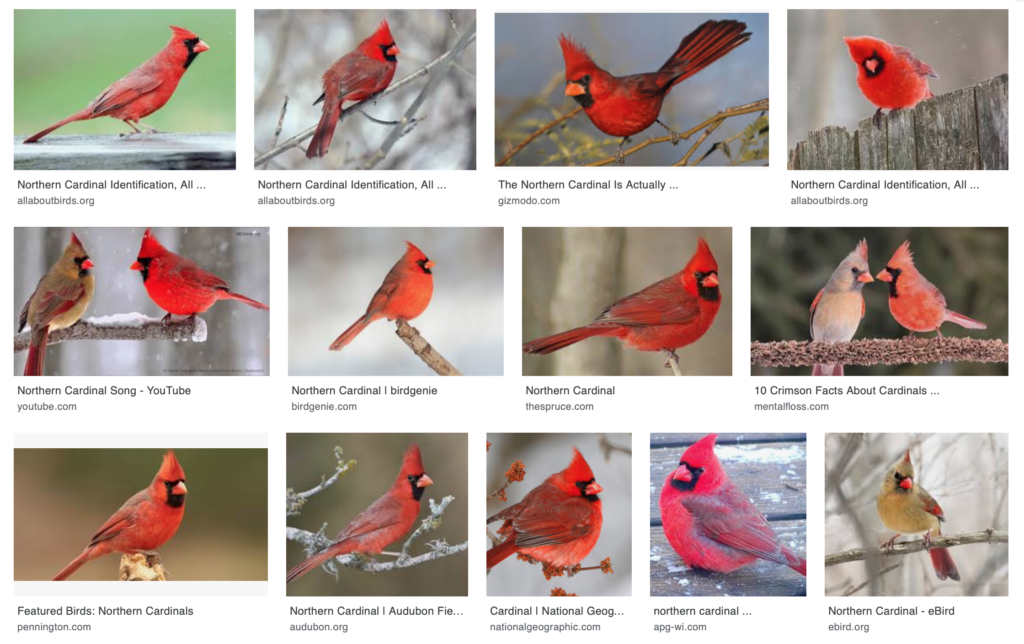

But there is also a lot of nature photography that remind me of the sport equivalent to hunting. Do a Google search for “cardinals” and you’ll see thousands of images. They show that the photographers were at the right place at the right time, they used perfect technique and excellent composition. But they all look the same, right?

To further illustrate this, a Google search for “Nature Photography” yields 3.4 billion results. At what point do we as photographers train our lenses on nature to illuminate and tell a new story?

Nature is Changing

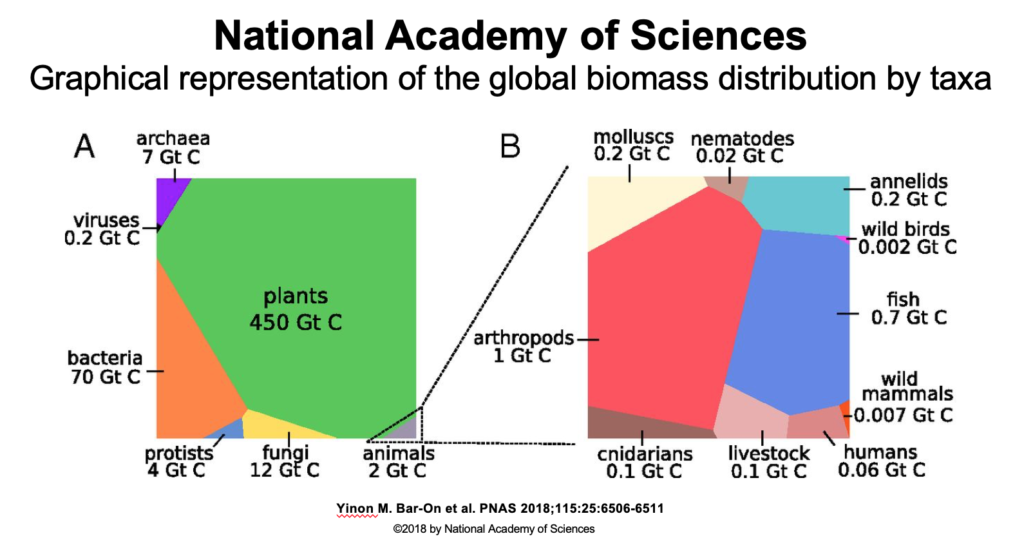

According to the National Academy of Sciences, the weight of 7.6 billion humans on the planet Earth makes up only 0.01% of all the biomass of the planet (plants make up 83%). Meanwhile, humans have caused the annihilation of 83% of all wild mammals, as well as half of all plants. Of all the birds which are left on the planet, about 70% are poultry chickens and other farmed birds. And out of the mammals that are left in the world, about 60% are livestock, 36% are pigs, and a mere 4% are wild.

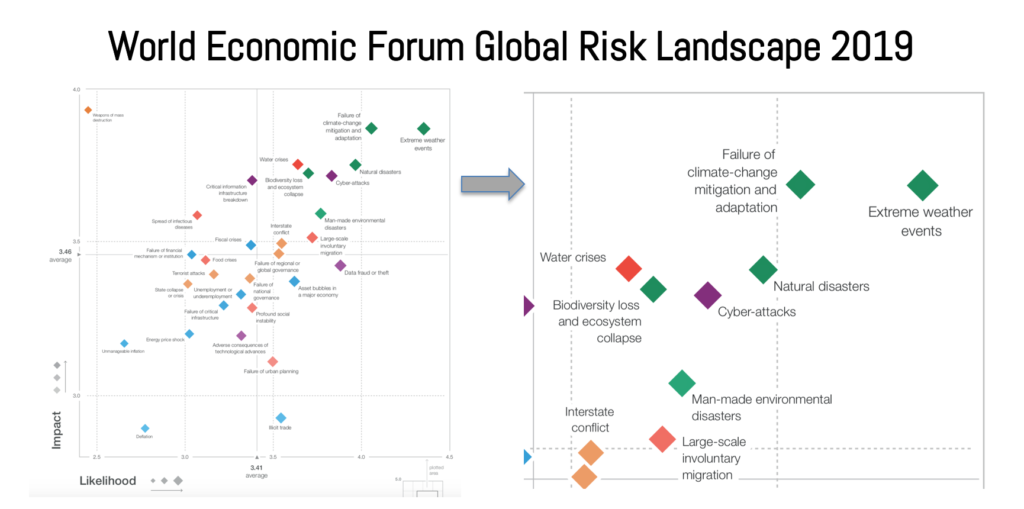

The World Economic Forum Global Risk Landscape in 2019 identifies extreme weather events, failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation, natural disasters, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse and water crisis as amongst the most pressing issues facing the planet. So, this begs the question about what we should be photographing and why we should be making pictures in the first place.

Searching for a New Definition

This got me to thinking about what is nature photography. Remember, I made an image of a maple leaf in my studio and didn’t really think about following any traditional rules that nature photographers have been trained to consider. Wikipedia has a definition of nature photography that highlights the aesthetic value which is often apparent in many nature images:

Nature photography is a wide range of photography taken outdoors and devoted to displaying natural elements such as landscapes, wildlife, plants, and close-ups of natural scenes and textures. Nature photography tends to put a stronger emphasis on the aesthetic value of the photo than other photography genres, such as photojournalism and documentary photography. “Nature photography” overlaps the fields of — and is sometimes considered an overarching category including — “wildlife photography,” “landscape photography,” and “garden photography”.

The Photographic Society of America (PSA)’s Nature Division Definition of Nature Photography emphasizes the story telling value of a photograph but discourages human elements except when they are integral parts of the nature story such as nature subjects, like barn owls or storks, adapted to an environment modified by humans. They don’t allow human created hybrid plants, cultivated plants, feral animals, domestic animal or mounted specimens. I’m not that familiar with PSA’s other competitions, but I assume they are addressing or considering the hand of man in nature photography.

I don’t see anything wrong with these definitions per se, but I don’t think they encourage the type of critical artistic investigation that is needed at a time when our natural world is in crisis. Perhaps it’s time to stop separating the hand of man in nature photography? I was pleasantly surprised to see that the Ward Museum did exactly that in their 2019 competition categories and I hope they continue to explore this subject in the future.

Finding Inspiration

As a fine art photographer, I look to create works that bring out the essence or nature of my subjects. Early in my photographic education, I was influenced by the work of Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Weston, and Imogen Cunningham. O’keeffe’s abstract paintings of flowers allowed me to see the essence and beauty of her subjects. Weston’s Pepper #30 forced me to look closely at the shape, texture, and uniqueness of his subject. Cunningham’s Calla Lily’s were meditations that captured my imagination.

In preparation for my lecture, I searched for examples of fine art photographers focused on nature and the nature of things. Paul Coghlin has an amazing series of dried flowers, which show a variety of specimens with incredible detail, shape and textures. I was delighted by the CHICken project by Monti and Tranchellini, extraordinary and beautiful images of chickens from around the world. Catherine Chalmer’s book, American Cockroach, focuses on a subject most of us are uncomfortable with, but one that is necessary and often overlooked. Joel Sartore is building a Photo Ark and documenting species before they become extinct.

Artists Jeff Louviere and Vanessa Brown explore the phenomenon of cymatics (visualizing sound) in their Resonantia project. Martin Klimas also captures images of sound in his series that looks like a 3-D take on Jackson Pollack. The impact of human activity on wildlife can be seen in the works of Neil Aldridge and Brian Skerry, while artists like Weston Fuller use photo illustration to explore the crisis of plastics in our oceans as well as David Maisel project, The Forest, which examines clear cutting of trees in Maine.

This is a small sampling of many artists seeking to go beyond the traditional definition of nature photography to tell a compelling story and I think we as photographers should follow their lead. While I think it is fine to keep the traditions of nature photography competitions, let’s begin to incorporate new ideas and approaches that may be beneficial to the natural world we love.